Much has been written in recent months about the increase in offshore rig utilization and dayrates.

With key segments of the fleet at 95% utilization or higher, dayrates for non-harsh environment jackup fixtures have surpassed $150,000, while floating rigs have been secured for contracts at or above $475,000. Right on cue, the talk of new rig orders has surfaced, but will it actually happen?

A lot has occurred since the last newbuilding cycle took place and there are several reasons why Westwood believes new rig construction will not happen anytime soon.

Assuming a rig owner can obtain financing, there are far fewer shipyards that would entertain building a new rig. Many have exited the business or undergone yard consolidation. As one drilling contractor put it, the yards are busy “building vessels they can actually get paid for,” referring to floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) and other non-drilling units. In addition, down payment terms, which had been as little as 2% in the last cycle, would be significantly higher now.

Secondly, there are still undelivered rigs in yards that were ordered in the last newbuilding period. While mostly completed, these “new” rigs require a substantial amount of capital and shipyard time. Nevertheless, there is still inventory available, another reason not to build now. Also related to excess inventory, several cold stacked units could undergo reactivation, providing rig owners with a cheaper and faster source for additional rigs.

Finally, there are more M&A deals that can be done. As seen in recent transactions, deals can be structured that do not require a lot of cash, making it far cheaper and faster to acquire a company and its assets versus building a new rig.

New floating rigs less likely

The prospect of building a new drillship or semisubmersible (semi) is less likely than jackups. Even with drillship dayrates inching closer to the magical $500,000 mark, the numbers simply do not add up at the present time.

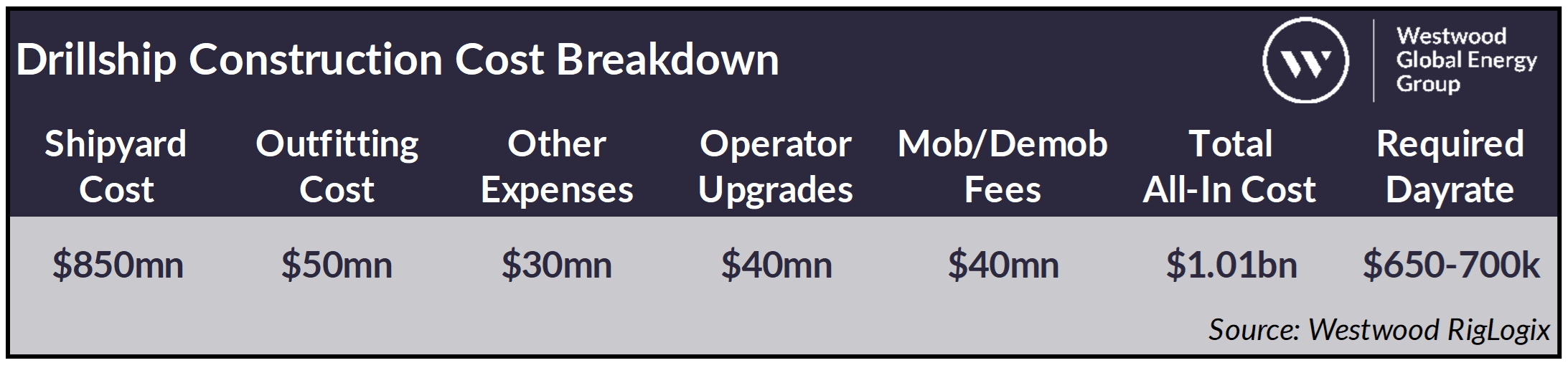

According to rig owner estimates, the all-in cost to build a new drillship would be over $1 billion. Assuming 90-95% utilization, the dayrate needed for a standard 12-15% return on investment (ROI) would be $650-700,000 for the useful life of the rig (~25 years). Build time would be around three years.

Drillship Construction Cost Breakdown (Image credit: Westwood RigLogix)

Drillship Construction Cost Breakdown (Image credit: Westwood RigLogix)

In addition to the economic factors, there are other notable reasons not to build. There are still 15 drillships and seven semis, many from the last newbuild cycle, waiting in various yards to be delivered (although three of the 22 units have contracts in place). Westwood believes as many as eight units may never be delivered, which leaves 11 newbuilds – seven drillships and four semis – available for rig owners to absorb into their fleets.

The investment required to get these units will vary, but the base cost is thought to be a minimum of $100-110 million (plus $250-300 million to buy the rig if necessary). With most of these units in Southeast Asia, a mobilisation fee would be as much as $35-50 million plus other upgrades necessary for a specific operator and/or region, adding another $30 million to the cost. So, excluding purchase price, an all-in cost of around $200 million would be expected. It is estimated to take 12-14 months of yard time to get one of these rigs out.

There are also 30 cold stacked floating rigs – 13 drillships and 17 semis. We believe as many as 10 are being marketed for drilling programs while a few will likely be scrapped. Between the stranded newbuilds and cold stacked units, rig owners have access to 30-35 units.

The cost to reactivate one of these rigs will vary depending on the scope of work done. For example, to reactivate a cold stacked drillship in Las Palmas, the base cost is believed to be $85-90 million alone, plus mobilization fees and additional upgrades. Shipyard time is believed to be around one year for reactivation.

A rig owner would need a minimum five-year initial term to even consider building a new unit and currently there are just a handful of regions where operators have programs that could offer that. Among the potential landing spots would be Brazil and Africa. TotalEnergies recently issued a tender for two drillships to work under 10-year contracts with rumors of two existing newbuilds competing for that work. The US Gulf of Mexico has taken on two newbuild drillships this year and last, but it seems unlikely the region could take on another.

The bottom line is that while it is conceivable that some new floating rig orders could eventually take place, a sustained period of significantly higher dayrates would be needed, and that, if it happens, is still a few years away.

Jackups more probable

Any new rig orders will likely be for jackups. Like floating rigs, multi-year contracts have been awarded, with some in the Middle East as long as 15 years. Dayrates have nearly doubled in the past year alone and reached as high as $160,000 in some areas. Two of the largest jackup owners, Borr Drilling and Shelf Drilling, say there is not enough equipment to fulfil future demand.

What about the cost to build a new jackup? It is estimated to be in the $250-300 million range for a 400ft-rated rig, depending on yard location. Delivery time is currently thought to be 2-2.5 years. According to jackup owners, an acceptable 15% ROI for a newbuild with 90-95% utilization would require a dayrate of $200-230,000 over the useful life (~25 years) of the rig.

In the current newbuild inventory there are 20 undelivered jackups, three of which have contracts and one has a pending sale. The remaining 16 units, ordered as early as 2013, have been mostly completed but would need shipyard time to finish construction and undergo acceptance testing.

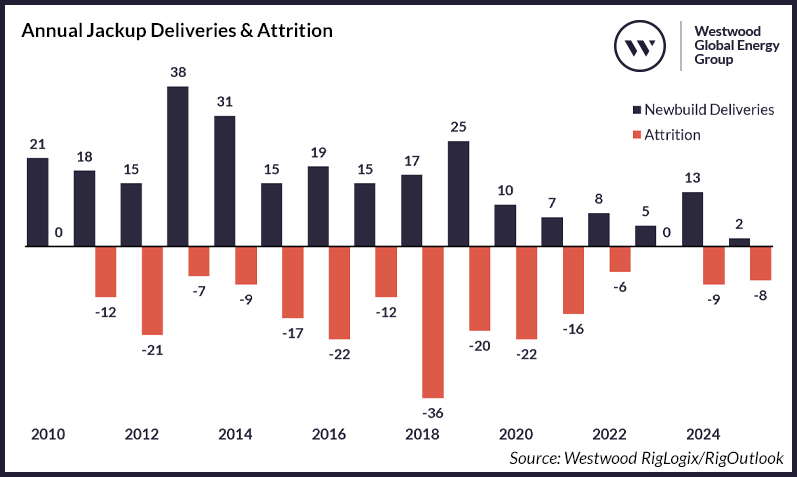

Annual Jackup Deliveries & Attrition. (Image credit: Westwood RigLogix/RigOutlook)

Annual Jackup Deliveries & Attrition. (Image credit: Westwood RigLogix/RigOutlook)

From 2010 to July 2023 the jackup fleet increased by a net of 45 rigs, with 245 deliveries and 200 units removed. Over the 14-year period, that is an average of three rigs per year, probably not as much as one might think. And with the current cold stacked numbers versus the number of rigs still under construction, the fleet size will decline on its current path.

Looking at the cold stacked fleet, 56 are available, but closer inspection shows the number available for reactivation is much lower. Six of the units have been stacked for over 10 years, making it highly unlikely they would ever work again. After removing units that due to design, water depth rating, age etc, would not likely be brought back into service, we believe there are fewer than 15-20 units as candidates to return to the fleet.

The cost to reactivate a stranded newbuild or cold stacked jackup varies depending on rig condition, age, time idle and level of preservation done prior to the rig going idle. Some recent reactivations have been completed for just under $20 million but estimates for other rigs pending reactivation are reported to be as much as $40 million. Required reactivation time is six to nine months depending on yard availability.

Despite the high price tag, it is not out of the question that some jackups will eventually be ordered. Of the current 438 marketed jackups in the global fleet, 100 are 40 years of age or more, 23% of the fleet. While fewer than 10 of the 100 are idle, it is doubtful that kind of usage can be sustained for many more years.

Rumors afoot indicate operator interest in newbuilds. A few super majors, citing current climbing rig costs, could reportedly offer initial contract terms that might entice rig owners to dip their toes in new construction. In addition, at least three jackups that previously retired with the intent of converting to wind farm installation vessels, will reportedly re-enter the fleet as drilling units.

Finally, ARO Drilling must be mentioned. In 2018, the company agreed to supply Saudi Aramco with 20 new jackups over a 10-year period. The first two were ordered in 2020, but none since. Delivery of those was scheduled for 2022 but slipped into this year after delayed completion of a new shipyard in Saudi Arabia to build the rigs. Assuming the remaining 18 rigs are ordered, it raises the question of whether there would be a need for additional newbuilds.

Westwood believes the reasons not to build a new rig outweigh the reasons to build at present. Although rig owners have historically not been known for their discipline, this time is different, or at least it appears to be. No speculative rig reactivations have been carried out and there does not seem to be any appetite to repeat the overbuilding mistakes of the past.

By Terry Childs, Head of RigLogix, Westwood Global Energy Group